On the contrary, opposites need one another, not only for definition, not only for complementarity, but in order to be. Their reciprocal need of one another is rooted in the very nature of totality.”

R.Gerhard, “Is modern music growing old?“ 1960

The Influence of the Spanish Civil War on Gerhard's Guitar Music

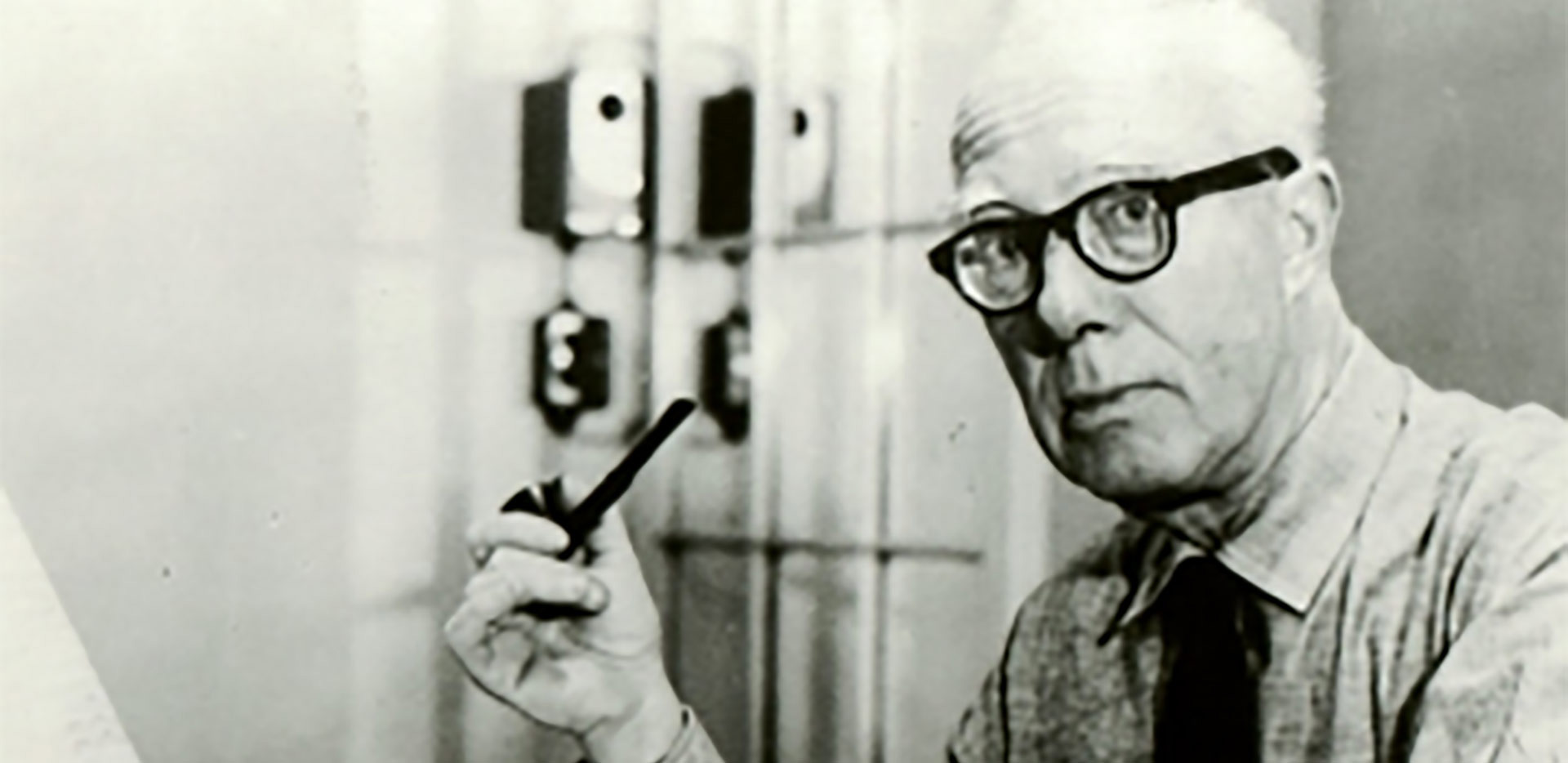

For several years, I have been deeply engaged in research on Roberto Gerhard, delving into his music for guitar and its connection to the Spanish Civil War. In 2021, I completed the recording of his complete guitar music for the Brilliant Classics label. Subsequently, in 2023, a chapter authored by me titled “The Influence of the Spanish Civil War on Gerhard’s Guitar Music” was included in the book “Roberto Gerhard: Reappraising a Musical Visionary in Exile.” Below is the abstract for the chapter:

“The Spanish Civil War marked a pivotal moment in Gerhard’s life, compelling him into exile. While away from his homeland, he staunchly maintained a pacifist stance and vehemently opposed Franco’s regime. The composer’s intimate connection with this tragic episode likely prompted the BBC to commission Gerhard for two pieces of incidental music based on significant literary works set during the Spanish Civil War: ‘The Revenge for Love’ (1957) and ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’ (1965). In both compositions, Gerhard chose to incorporate the guitar, an instrument deeply intertwined with Spanish and Catalan culture. This chapter explores how Gerhard’s political convictions and experiences during the Spanish Civil War influenced his compositions, particularly ‘The Revenge for Love’ and ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls,’ which also served as the inspiration for his seminal guitar works: the Fantasia for solo guitar and the chamber piece ‘Libra.’ Additionally, the chapter delves into the intricate genesis of the Fantasia for solo guitar, elucidating how Gerhard, drawing from the musical material of ‘The Revenge for Love,’ crafted two versions of the composition—an initial version rejected by guitarist Julian Bream and a subsequent iteration that was eventually published and premiered by John Williams.”

Continuing my research, I have actively participated in various research conferences. Furthermore, I have delved deeper into Gerhard’s profound interest in psychoanalysis, which he cultivated through extensive reading and interactions with prominent experts. This interest is proposed to have significantly influenced his creative process, transforming composition into a tool for self-analysis that melds unbridled subconscious expression with rationality.

A burgeoning interest in interpreting Gerhard’s music symbolically, particularly in relation to the Spanish Civil War, has become a prominent theme in Gerhard scholarship. This interest has found notable expression in the book “Roberto Gerhard: Reappraising a Visionary Composer in Exile,” edited by Rachael Mann and Monty Adkins. In this seminal work, numerous scholars have contributed to reshaping our understanding of Gerhard’s role as an exiled composer. I have explored how his guitar music serves as a poignant reflection of his experiences during the Spanish Civil War and his protracted illness.

Nevertheless, the increasing recognition of the link between Gerhard’s music and his personal experiences appears to contradict his self-professed description of his music as abstract and devoid of conscious descriptive references. This paradox raises a fundamental question: can both perspectives coexist harmoniously? In essence, can his music simultaneously embody abstraction and be rooted in personal experiences? This intriguing conundrum fuels lively discussions within the realm of music research, presenting an enticing challenge for scholars endeavoring to unravel the intricacies of Gerhard’s creative process.

The prevailing tendency in research to view the compositional process as a series of conscious decisions made by the composer may pose a fundamental challenge in comprehending Gerhard’s work thus far. Indeed, for Gerhard, composition was not merely a rational decision-making process; rather, it involved a dynamic interplay between rational and unconscious impulses, with the latter predominantly driving the creative endeavor while the former served as a conduit for its expression.

I posit that Gerhard intentionally developed his later compositional method, drawing inspiration from psychoanalysis and graphology, to facilitate the uninhibited expression of his subconscious. While his music retained its abstract essence, the compositional process enabled the emergence of symbolic elements from his subconscious that might have eluded conventional linguistic or rational articulation. These elements can be likened to the revelations gleaned through psychoanalytical examinations of dreams or, as exemplified in Gerhard’s liner notes for ‘Libra,’ the unveiling of an individual’s character through handwriting—an endeavor deeply rooted in the subconscious realm.

“The fact is that between creative activity and theoretical speculation there is a tremendous gap which none of us – whether artist or theorist – can possibly bridge. This all springs from the fact that the creative state of mind is basically different from the critical state of mind.”

R. Gerhard, Music and Ballet

Further Research on Gerhard's Music

Gerhard's profound interest in psychoanalysis

Composing as research tool

In addition to the research I am exploring this research through compositions and arrangement. As outputs will feature a recording of Gerhard’s incidental piece For Whom the Bells Toll, transformed into a concert piece. A new arrangement of this work that I already recorded a few years ago, applying my interpretation of Gerhard’s compositional approach, characterised by a balance between intuition and rationality. A second output will be a video of my original composition, Fantasia, a tribute to Gerhard. This composition represents my endeavor to intuitively explore Gerhard through the creation of new music. This creative process involved embracing both rational and completely intuitive components that I not have fully comprehended. Analyzing their interplay within my composition has been instrumental in deepening my understanding of both myself and the profound fascination Gerhard held for me as a researcher. The reflections on my composition were the initial inspiration behind this paper, but to be in line with the approach of Gerhard I will not attempt to define the music or to give description in this paper.

While this aspect of the research may appear unconventional to those accustomed to traditional musicological articles, it is an integral part of my approach. I employ my composition to gain intuitions. I try to alternate between creative and critical states of mind. Gerhard himself observed that these two states reveal different realities, and rather than favoring one over the other, my aim is to let them coexist and explore their interrelations.